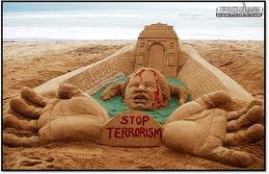

Photo credit:www.picdesi.com

Written by Garima Tiwari

“Terrorism often thrives where human rights are violated,” and “the lack of hope for justice provides breeding grounds for terrorism.”[i] The recent February 2013 blasts in Hyderabad, India have brought to light the weakness of the intelligence and the laws to create any deterrence. After 9/11, the threat from terrorism has been identified as the most dangerous threat by states. This is because of the unpredictability, widespread reach, lethality and ruthlessness of the attacks. The trend toward higher casualties reflects the changing motivation of today’s terrorists. Terrorist groups lack a concrete political goal other than to punish their enemies.

The Hyderabad blasts are a stark reminder of the shortcomings of Indian counter-terrorism capabilities. Since 2008, India has had 11 more terror strikes in which 60 people have been killed across five cities. The government has taken measures to beef up its security and intelligence agencies. But implementation on the ground is often stymied by India’s notorious bureaucratic red tape. The Maharashtra Anti-Terrorism squad, for example, has a capacity of 935 personnel but is actually working with just 300. A $28.5 million proposal to improve security around Mumbai was announced soon after the 2008 “26/11″ attack—involving 5,000 CCTV cameras at key junctions, motion detectors, night vision for security forces, thermal imaging for the police, and vehicle license plate identification capability. But it never took off. [ii]

The whole counter –terrorism strategy involves a democratic dilemma which consists of two parts. The first is how to be effective in counter-terrorism while still preserving liberal democratic values , and the second is how to allow the government to fulfill its first and foremost responsibility of protecting the lives of its citizens without using the harsh measures at its disposal.[iii] It is generally assumed that the ‘criminal justice model’ is the better option for democracies to overcome the ‘democratic dilemma’ they face. Terrorism inevitably involves the commission of a crime. Since democracies have well-developed legislations, systems and structures to deal with crime, the criminal justice system should be at the heart of their counter-terrorism efforts.[iv] But then special laws with higher deterrence values are required and justified, on the grounds that the existing criminal laws are not adequate to deal with the militancy because what is at stake is the very existence of state and another reason cited is the obligations under the prevailing international environment and obligations like under Prevention of Terrorism Act in India after the 9/11 attack and the UN Resolution 1373. Then there are security forces empowerment laws in India that give immunity and additional special powers to the security forces like the Armed Forces Special Powers Act; Laws of proscription that criminalises terrorist groups and a range of undesirable activities like the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and other exclusive laws on control of finances, money laundering, drug-trafficking, cyber warfare and so on. [v] Counter-terror laws in India have come into being reflecting the Indian style of handling terrorism – namely, ad hocism. No single law has prevailed throughout. From time to time, depending on the regime at the Center, legislation has come into being and then faded.

When one tries to look at the counter-terror laws of India the following characteristics would come to picture which actually highlight various aspects of where the democratic dilemma is leading:

- Hasty enactment without giving much room for public debate or judicial scrutiny;

- Overly broad and ambiguous definitions of terrorism that fail to satisfy the principle of legality;

- Pre-trial investigation and detention procedures which infringe upon due process, personal liberty, and limits on the length of pretrial detention;

- Special courts and procedural rules that infringe upon judicial independence and the right to a fair trial;

- Provisions that require courts to draw adverse inferences against the accused in a manner that infringes upon the presumption of innocence;

- Lack of sufficient oversight of police and prosecutorial decision-making to prevent arbitrary, discriminatory, and disuniform application; and

- Broad immunities from prosecution for government officials who fail to ensure the right to effective remedies.[vi]

Despite the experience of 26/11, India’s internal security still remains vulnerable because we have not acquired appropriate capacities and determination to prevent such an exigency. The laws emphasise more on protection of state rather than people. The Indian politicians do not accept national security with the kind of gravitas it demands.[vii] Overall, neither the laws create deterrence nor do they protect the lives of civilian population.

What is needed in not just a strong all encompassing law, but strict implementation and vigilance with respect for human rights. There have to be proper safeguards against misuse and abuse of law. There has to be clear cut definitions of crimes and penal provisions to avoid excessive discretionary powers. Enactment of special laws should not be in haste; for greater awareness and acceptance, the process has to be transparent and should be subject to public debate and judicial scrutiny. Special laws should possess review mechanisms and ‘sun-set’ clauses for periodic assessments.[viii] Most experts have suggested strengthening policing from the grass root level, enacting tough laws and speedy trial of cases would go a long way in preventing and controlling terror attacks in the country because the terror attacks are often carried out with the help of some local elements. Then again the external factors like politicisation of the police force should be checked to ensure its effectiveness.[ix]

Terrorism is a threat which most states are today facing. We can only defeat terrorism in the long term by preventing the next generation of terrorists from emerging. We must reduce the breeding grounds of terrorism. This is, of course, not an easy task.[x]

[i] Supreme Court of India in People’s union for Civil Liberties vs. union of India, AIR 2004 SC 456, 465

[ii] Hyderabad’s Terror Attack: Speculation Swirls as Critics Point to Government Failure

By Nilanjana Bhowmick Feb. 22, 2013available at http://world.time.com/2013/02/22/hyderabads-terror-attack-speculation-swirls-as-critics-point-to-government-failure/#ixzz2P8YZGrFd

[iii] Excerpt by Boaz Ganor, Trends in International Terrorism and Counter Terrorism, Editors: Dr. Boaz Ganor and Dr. Eitan Azani available at http://www.ict.org.il/Books/TrendsinInternationalTerrorism/tabid/282/Default.aspx

[iv] Lindsay Clutterbuck, “Law Enforcement,” in Audrey Kurth Cronin and James M Ludes (eds.), Attacking Terrorism – Elements of a Grand Strategy (washington, D.C.: Georgetown university Press, 2004), p. 141

[v] Dr. N. Manoharan, Special Laws to Counter Terrorism in India: A Reality Check available at http://www.vifindia.org/article/2012/november/20/special-laws-to-counter-terrorism-in-india-a-reality-check

[vi] Anil Kalhan et al, “Colonial Continuities: Human Rights, Terrorism and Security Laws in India,” Colombia Journal of Asian Law, Vol. 20, no. 1, 2006, p. 96.

[vii] C. Uday Bhaskar, former director of the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses, a New Delhi-based think tank available at http://world.time.com/2013/02/22/hyderabads-terror-attack-speculation-swirls-as-critics-point-to-government-failure/#ixzz2P8Y5pFI3

[viii] N. Manoharan, Trojan Horses? Efficacy of Counter-terrorism Legislation in a Democracy Lessons from India, Manekshaw PaPer No.30 , 2011, available at http://www.claws.in/administrator/uploaded_files/1308896190MP%2030.pdf

[ix] Strong local policing, strict laws will curb terror attacks’, Tuesday, 26 February 201, available at http://www.siasat.com/english/news/strong-local-policing-strict-laws-will-curb-terror-attacks

[x] Excerpt Gijs de Vries, Trends in International Terrorism and Counter Terrorism, Editors: Dr. Boaz Ganor and Dr. Eitan Azani available at http://www.ict.org.il/Books/TrendsinInternationalTerrorism/tabid/282/Default.aspx